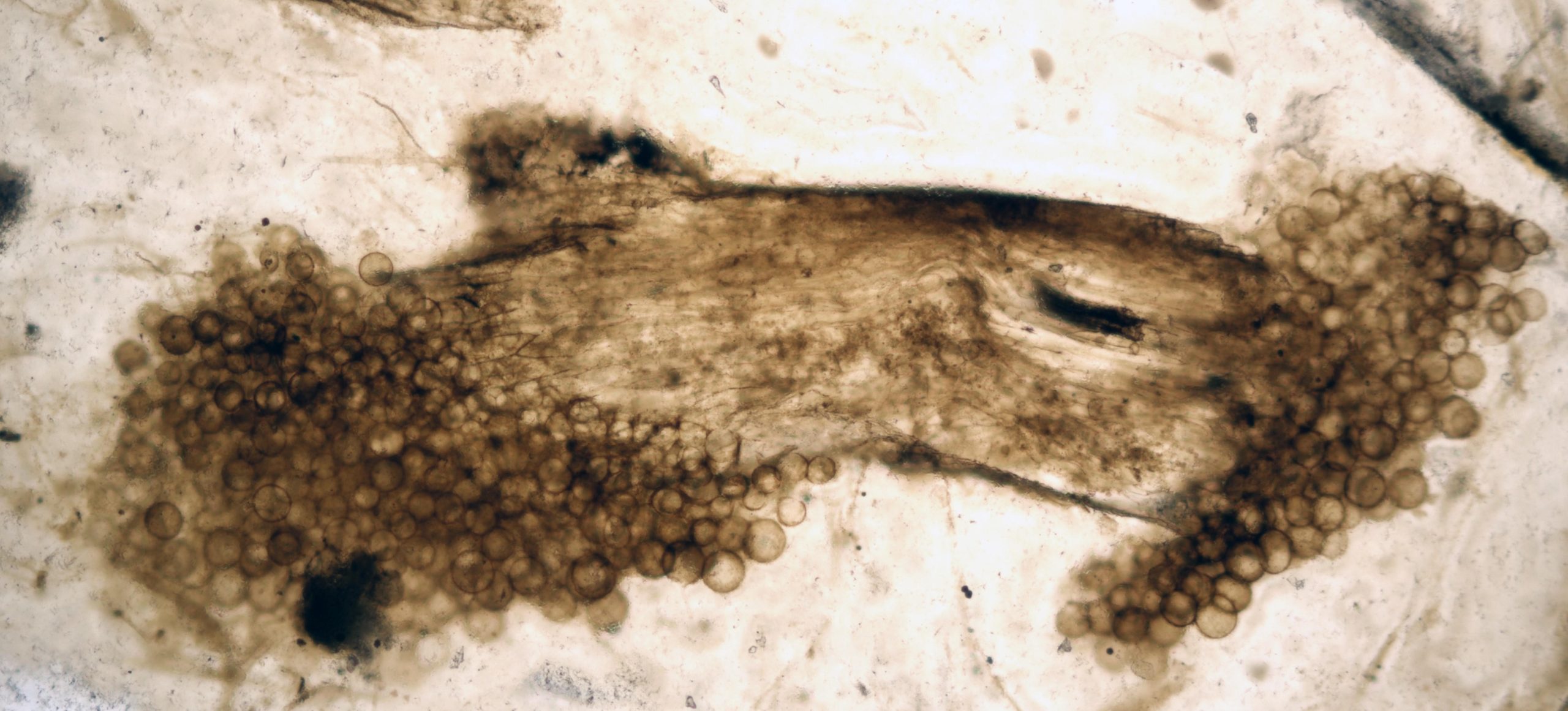

Un piccolo pezzo di pianta fossile del Reno con funghi fossili che colonizzano gli arti, visto al microscopio. Credito: Loron et al.

Una tecnologia all’avanguardia ha rivelato nuove intuizioni su un tesoro fossile famoso in tutto il mondo, che potrebbe fornire importanti indizi sulla prima vita sulla Terra.

Gli scienziati che studiano il deposito di fossili di 400 milioni di anni fa, portato alla luce nella remota regione nord-orientale della Scozia, riferiscono che i loro risultati mostrano un livello di conservazione molecolare più elevato in questi fossili rispetto a quanto previsto in precedenza.

Un nuovo esame del tesoro squisitamente conservato dell’Aberdeenshire ha permesso agli scienziati di identificare le impronte chimiche dei vari organismi al suo interno.

Proprio come la Stele di Rosetta ha aiutato gli egittologi a tradurre i geroglifici, il team spera che questi simboli alchemici aiutino a comprendere meglio l’identità delle forme di vita, che sono rappresentate da altri fossili più oscuri.

Scoperto vicino al villaggio di Rhynie nell’Aberdeenshire nel 1912, lo straordinario ecosistema fossile è mineralizzato e ricoperto di roccia dura composta da silice. Conosciuto come Rhynie chert, ha origine nel primo periodo Devoniano – circa 407 milioni di anni fa – e ha un ruolo importante nella comprensione della vita sulla Terra da parte degli scienziati.

I ricercatori hanno combinato le ultime novità in termini di imaging non distruttivo, analisi dei dati e[{” attribute=””>machine learning to analyze fossils from collections held by National Museums Scotland and the Universities of Aberdeen and Oxford. Scientists from the University of Edinburgh were able to probe deeper than has previously been possible, which they say could reveal new insights about less well-preserved samples.

Employing a technique known as FTIR spectroscopy – in which infrared light is used to collect high-resolution data – researchers found impressive preservation of molecular information within the cells, tissues, and organisms in the rock.

Since they already knew which organisms most of the fossils represented, the team was able to discover molecular fingerprints that reliably discriminate between fungi, bacteria, and other groups.

These fingerprints were then used to identify some of the more mysterious members of the Rhynie ecosystem, including two specimens of an enigmatic tubular “nematophyte”.

These strange organisms, which are found in Devonian – and later Silurian – sediments have both algal and fungal characteristics and were previously hard to place in either category. The new findings indicate that they were unlikely to have been either lichens or fungi.

Dr. Sean McMahon, Chancellor’s Fellow from the University of Edinburgh’s School of Physics and Astronomy and School of GeoSciences, said: “We have shown how a quick, non-invasive method can be used to discriminate between different lifeforms, and this opens a unique window on the diversity of early life on Earth.”

The team fed their data into a machine learning algorithm that was able to classify the different organisms, providing the potential for sorting other datasets from other fossil-bearing rocks.

The study, published in Nature Communications, was funded by The Royal Society, Wallonia–Brussels International, and the National Council of Science and Technology of Mexico.

Dr Corentin Loron, Royal Society Newton International Fellow from the University of Edinburgh’s School of Physics and Astronomy said the study shows the value of bridging paleontology with physics and chemistry to create new insights into early life.

“Our work highlights the unique scientific importance of some of Scotland’s spectacular natural heritage and provides us with a tool for studying life in trickier, more ambiguous remnants,” Dr. Loron said.

Dr. Nick Fraser, Keeper of Natural Sciences at National Museums Scotland, believes the value of museum collections for understanding our world should never be underestimated.

He said: “The continued development of analytical techniques provides new avenues to explore the past. Our new study provides one more way of peering ever deeper into the fossil record.”

Reference: “Molecular fingerprints resolve affinities of Rhynie chert organic fossils” by C. C. Loron, E. Rodriguez Dzul, P. J. Orr, A. V. Gromov, N. C. Fraser and S. McMahon, 13 March 2023, Nature Communications.

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-023-37047-1

“Appassionato pioniere della birra. Alcolico inguaribile. Geek del bacon. Drogato generale del web.”